Introduction

One of our customers asked for the security review of its High Performance Computing (HPC) infrastructure. During the assessment, the auditor discovered a buffer overflow vulnerability within the authentication daemon of the cluster, Munge. This bug has been present in the codebase for approximately 20 years and every version up to 0.5.17 are impacted. This vulnerability can be exploited locally to leak the Munge secret key, allowing attacker to forge arbitrary Munge token, valid across the cluster. In a way, this is a Local Privilege Escalation in the context of High Performance Computers. This article will provide some understanding about how High Performance Computers work in general, and give a quick overview of Slurm and Munge. If you are not interested in HPC, you can directly jump to the exploitation part.

Context

HPCs

What is HPC ? How does it work ?

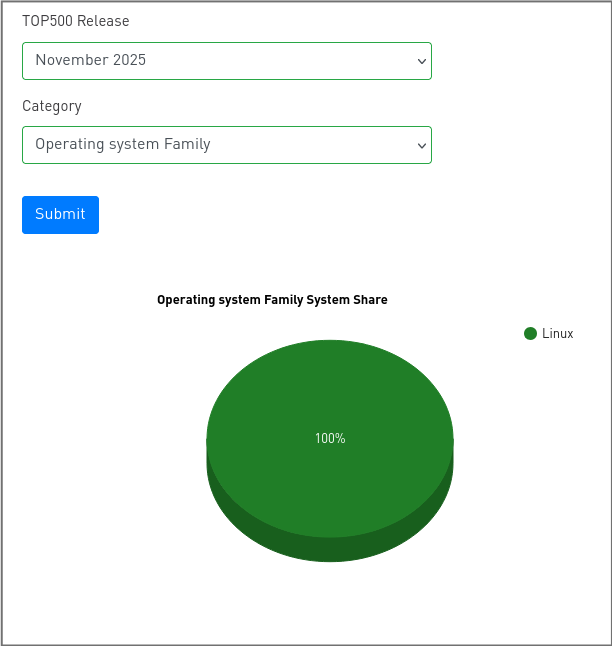

Nowadays, an HPC-er is just a fancy name for a big cluster of Linux machines.

That being said, let's give a bit more details about how they work. HPC-er should not be seen as 1 machine with a superfast CPU. It is a cluster of many computing machines, called computing nodes, designed to run parallelizable jobs.

A group of machine does not automatically become an HPC-er. An HPC-er is defined as follows:

A certain homogeneity amongst the computing nodes: They must all run the same software stack and offers approximately the same hardware. All nodes do not need to be the same, but they can be grouped by hardware capabilities: GPUs, FPGA... The general idea is that group of similar nodes can replace each others. A computing job is not written to work on one specific node. It must be able to run on the entire cluster.

A high bandwidth, low latency interconnection between computing nodes: Computing nodes are linked together using dedicated technologies. HPC-er being composed of many computing nodes, it is very important that these nodes communicate effectively to synchronize job progress, or share processing data.

An orchestration/scheduling mechanism to distribute jobs on the cluster: To be able to distribute jobs effectively on the computing nodes, they need to be orchestrated. A scheduler is responsible for dispatching new jobs to available nodes and ensure fairness between users. Many different schedulers exist, one of the most commonly used is Slurm, Quoting Schedmd, the company behind Slurm, approximately 65% of all HPC-er in the world uses it. Its main role is to allocate computing resources, such as CPUs, memory, and GPUs, to users’ jobs in an efficient and fair way. Users submit jobs to Slurm, specifying the resources they need, and Slurm decides when and where these jobs will run based on availability and scheduling policies. By managing job queues and resource usage across a cluster, Slurm helps maximize system utilization while ensuring that multiple users can share the HPC infrastructure smoothly. When launching a computing job on the HPC-er, the user does not choose which set of nodes it is going to run on.

Therefore, Slurm is a critical component, as it plays the role of a kind of "meta" operating system, for a "meta" computer made up of multiple machines. The security bug discovered here impacts Munge, the authentication daemon used by default in Slurm installation.

Slurm and Munge

To understand the impact and exploitability of the security bug, a quick overview of Slurm and Munge is necessary.

Slurm job creation

First of all, note that HPC-er are often multi-user computers. For example, a research institute manages an HPC and allows every researcher to use it. The standard workflow of user on a Slurm controlled HPC-er is the following:

- researcher A connects using SSH on a first machine dedicated to submit jobs to the cluster.

- From there, it uses command such as srun, salloc to request nodes and start/enqueue new jobs.

- These commands interact through a custom protocol with Slurmctld, often running on another machine. This is the scheduler daemon

- Slurmctld return the list of available nodes to the user.

- Then for every available nodes, srun asks the local Slurm agent, Slurmd, to start a linux process as researcher A.

For Slurm, a job is a linux process running on multiple nodes. In the previous example, researcher A run the following command:

$ srun id

uid=1032(researcher A) gid=1032(researcher A) groups=1032(researcher A)

Each allocated node will run its own /usr/bin/id, it is very important to ensure homogeneity of the computing nodes.

Shared File System: Most of the time, to allow nodes to access the same file system, the HPC-er nodes will mount the same NFS share, exposing, for example, the home of each user. In NFS context, access control is managed through Unix UID/GID mechanism.

Authentication mechanism - Munge

In order to authenticate a user across the entire HPC-er, Slurm relies on Munge.

MUNGE (MUNGE Uid 'N' Gid Emporium) is an authentication service for creating and validating user credentials. It is designed to be highly scalable for use in an HPC cluster environment. It provides a portable API for encoding the user's identity into a tamper-proof credential that can be obtained by an untrusted client and forwarded by untrusted intermediaries within a security realm. Clients within this realm can create and validate credentials without the use of root privileges, reserved ports, or platform-specific methods. - Munge's README

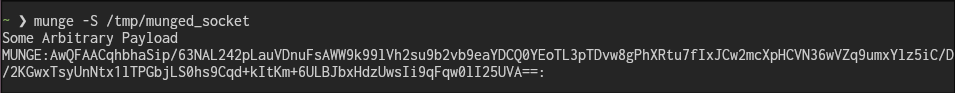

Each node of the HPC-er, including the submit node, the scheduler node and the computing nodes, runs a munge server, called munged. The same private key is deployed across all nodes. A user, on a node can ask its local munged server to generate a ticket. A munge ticket is made up of uid/gid of the requesting user, a timestamp and in some case, a user specified payload.

To communicate with client, munged exposes a UNIX socket. Client can connect to this socket through the munge/unmunged binaries or using the libmunge.

mungeSlurmd and Slurmctld use these tokens to authenticate the users before starting jobs. This ensures that only researcher A can start a job as researcher A on a computing node.

Actually, the username is never stored on the ticket, only UNIX uid/gid. In a context where ACLs are managed through UID/GID, like NFS, this is the key mechanism to protect users data and computings.

Design weakness ?

If an attacker manages to elevate it privileges on one single node of the cluster, it can leak the munge key and impersonate any other users for the entire cluster. The risk is accepted as almost every node is the same and a privilege escalation on one node would normally work on other nodes. However this design makes Munged a particularly interesting component. Leaking the secret key allows attacker to start job as any users on any node by submitting a job the slurm agent of a computing node with forged credentials.

In the most secure configuration, the local Slurm agent, SlurmD, refuses to start new job as

root. This may still be exploited by forging tickets for system administrators, taking advantage of their sudo rights for example.

Finding the vulnerability

American Fuzzy Lop

The problem with a 5 day pentest is that you don't have the time to read the source code of every components. Luckily, it has been some time since computer can find the vulnerabilities by themselves.

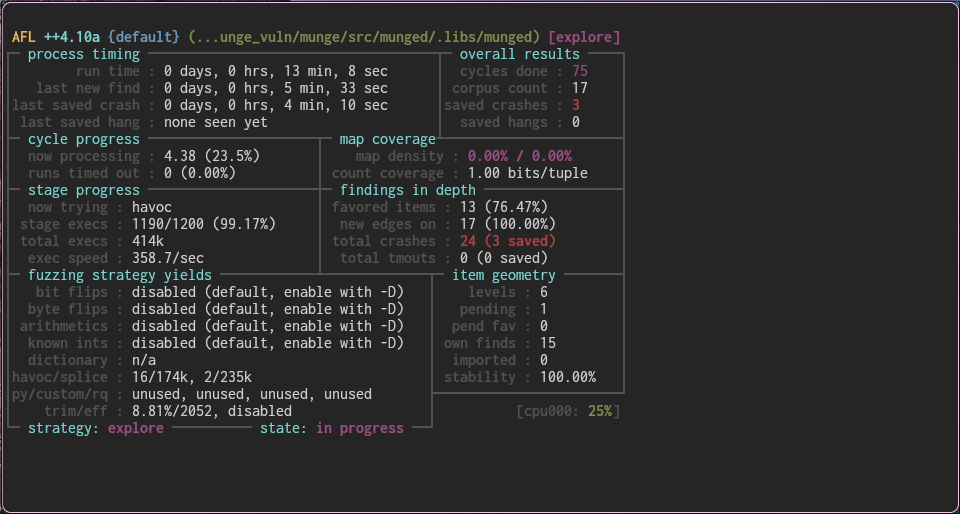

When reading through the documentation provided by our customer on the first day of the assessment, Munge appeared to be one of the most critical component of the HPC. After a quick look at its source code, the auditor decided it was worth investigating. Because a whole pentest still had to be done, and after a discussion with another colleague, it was decided to use AFL to fuzz Munged message parsing and encoding/decoding routines. It did not take too much time to produce a harness by simply copying the job_exec function of munged into main.

int

main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

conf = create_conf ();

uint8_t *buf;

ssize_t len;

m_msg_t m;

m = malloc(sizeof(struct m_msg));

munge_err_t e;

printf("sizeof(struct munge_cred) = %d\n", sizeof(struct munge_cred));

printf("sizeof(struct m_msg) = %d\n", sizeof(struct m_msg));

printf("sizeof(struct conf) = %d\n", sizeof(struct conf));

e = m_msg_recv (m, MUNGE_MSG_UNDEF, MUNGE_MAXIMUM_REQ_LEN);

if (e == EMUNGE_SUCCESS) {

switch (m->type) {

case MUNGE_MSG_ENC_REQ:

enc_process_msg (m);

break;

case MUNGE_MSG_DEC_REQ:

dec_process_msg (m);

break;

default:

m_msg_set_err (m, EMUNGE_SNAFU,

strdupf ("Invalid message type %d", m->type));

break;

}

}

/* For some errors, the credential was successfully decoded but deemed

* invalid for policy reasons. In these cases, the origin IP address

* is added to the error message to aid in troubleshooting.

*/

char* p;

if (m->error_num != EMUNGE_SUCCESS) {

p = (m->error_str != NULL)

? m->error_str

: munge_strerror (m->error_num);

switch (m->error_num) {

case EMUNGE_CRED_EXPIRED:

case EMUNGE_CRED_REWOUND:

case EMUNGE_CRED_REPLAYED:

if (m->addr_len == 4) {

char ip_addr_buf [INET_ADDRSTRLEN];

if (inet_ntop (AF_INET, &m->addr, ip_addr_buf,

sizeof (ip_addr_buf)) != NULL) {

log_msg (LOG_DEBUG, "%s from %s", p, ip_addr_buf);

break;

}

}

log_msg (LOG_DEBUG, "%s", p);

break;

default:

log_msg (LOG_INFO, "%s", p);

break;

}

}

m_msg_destroy (m);

out:

free(buf);

return 0;

}

Then, fuzzing only require to replace functions receiving data on the Unix Socket by reads from the stdin.

A small corpus of 2 messages can be feed to AFL:

- A ticket creation request, called encoding in munge language.

- A ticket verification request, referred as decoding request.

With this corpus after few minutes, AFL found multiple crashes.

The analysis of the crash corpus allows us to understand the root cause of the bug.

Root Cause Analysis

It is recommended to follow this analysis with the source code of Munge.

The crash occurs in the m_msg_destroy when freeing invalid pointer of the struct m_msg.

file: src/libcommon/m_msg.c :

void

m_msg_destroy (m_msg_t m)

{

/* Destroys the message [m].

*/

assert (m != NULL);

if (m->sd >= 0) {

(void) close (m->sd);

}

if (m->pkt && !m->pkt_is_copy) {

assert (m->pkt_len > 0);

free (m->pkt);

}

if (m->realm_str && !m->realm_is_copy) {

assert (m->realm_len > 0);

free (m->realm_str);

}

if (m->data && !m->data_is_copy) {

assert (m->data_len > 0);

free (m->data);

}

if (m->error_str && !m->error_is_copy) {

assert (m->error_len > 0);

free (m->error_str);

}

if (m->auth_s_str && !m->auth_s_is_copy) {

assert (m->auth_s_len > 0);

free (m->auth_s_str);

}

if (m->auth_c_str && !m->auth_c_is_copy) {

assert (m->auth_c_len > 0);

free (m->auth_c_str);

}

free (m);

return;

}

This struct m_msg is allocated dynamically by the main thread when a new client connects to the UNIX Socket. This structure represents the current message to be processed. It holds plenty of data, such as request type, UID/GID of the requesting process and many pointers.

The main thread does not directly parse the message sent by the client. Instead it adds the current struct m_msg to a list of work to be done, it wakes up a worker thread, and all the parsing logic will be done by the worker.

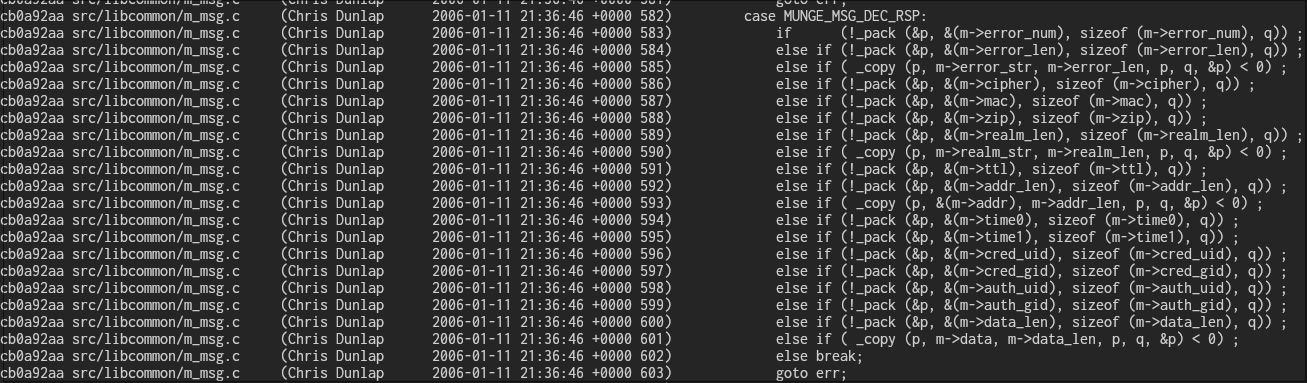

The parsing logic is implemented in _msg_unpack an internal function called by the m_msg_recv in file src/libcommon/m_msg.c.

This function is exposed by the libcommon which is used by both

mungeclient andmungedserver. Thus, it expects any type of messages despite server only receiving requests and client only receiving responses.

file: src/libcommon/m_msg.c

static munge_err_t

_msg_unpack (m_msg_t m, m_msg_type_t type, const void *src, int srclen)

{

/* Unpacks the message [m] from transport across the munge socket.

* Checks to ensure the message is of the expected type [type].

*/

m_msg_magic_t magic;

m_msg_version_t version;

void *p = (void *) src;

void *q = (unsigned char *) src + srclen;

assert (m != NULL);

switch (type) {

case MUNGE_MSG_HDR:

if (!_unpack (&magic, &p, sizeof (magic), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&version, &p, sizeof (version), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->type), &p, sizeof (m->type), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->retry), &p, sizeof (m->retry), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->pkt_len), &p, sizeof (m->pkt_len), q)) ;

else break;

goto err;

case MUNGE_MSG_ENC_REQ:

if (!_unpack (&(m->cipher), &p, sizeof (m->cipher), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->mac), &p, sizeof (m->mac), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->zip), &p, sizeof (m->zip), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->realm_len), &p, sizeof (m->realm_len), q));

else if (!_alloc ((vpp) &(m->realm_str), m->realm_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->realm_str, p, m->realm_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->ttl), &p, sizeof (m->ttl), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->auth_uid), &p, sizeof (m->auth_uid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->auth_gid), &p, sizeof (m->auth_gid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->data_len), &p, sizeof (m->data_len), q)) ;

else if (!_alloc (&(m->data), m->data_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->data, p, m->data_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else break;

goto err;

case MUNGE_MSG_ENC_RSP:

if (!_unpack (&(m->error_num), &p, sizeof (m->error_num), q));

else if (!_unpack (&(m->error_len), &p, sizeof (m->error_len), q));

else if (!_alloc ((vpp) &(m->error_str), m->error_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->error_str, p, m->error_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->data_len), &p, sizeof (m->data_len), q)) ;

else if (!_alloc (&(m->data), m->data_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->data, p, m->data_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else break;

goto err;

case MUNGE_MSG_DEC_REQ:

if (!_unpack (&(m->data_len), &p, sizeof (m->data_len), q)) ;

else if (!_alloc (&(m->data), m->data_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->data, p, m->data_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else break;

goto err;

case MUNGE_MSG_DEC_RSP:

if (!_unpack (&(m->error_num), &p, sizeof (m->error_num), q));

else if (!_unpack (&(m->error_len), &p, sizeof (m->error_len), q));

else if (!_alloc ((vpp) &(m->error_str), m->error_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->error_str, p, m->error_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->cipher), &p, sizeof (m->cipher), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->mac), &p, sizeof (m->mac), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->zip), &p, sizeof (m->zip), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->realm_len), &p, sizeof (m->realm_len), q));

else if (!_alloc ((vpp) &(m->realm_str), m->realm_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->realm_str, p, m->realm_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->ttl), &p, sizeof (m->ttl), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->addr_len), &p, sizeof (m->addr_len), q)) ;

else if ( _copy (&(m->addr), p, m->addr_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->time0), &p, sizeof (m->time0), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->time1), &p, sizeof (m->time1), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->cred_uid), &p, sizeof (m->cred_uid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->cred_gid), &p, sizeof (m->cred_gid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->auth_uid), &p, sizeof (m->auth_uid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->auth_gid), &p, sizeof (m->auth_gid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->data_len), &p, sizeof (m->data_len), q)) ;

else if (!_alloc (&(m->data), m->data_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->data, p, m->data_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else break;

goto err;

case MUNGE_MSG_AUTH_FD_REQ:

if (!_unpack(&(m->auth_s_len), &p, sizeof(m->auth_s_len), q));

else if (!_alloc((vpp)&(m->auth_s_str), m->auth_s_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->auth_s_str, p, m->auth_s_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack(&(m->auth_c_len), &p, sizeof(m->auth_c_len), q));

else if (!_alloc((vpp)&(m->auth_c_str), m->auth_c_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->auth_c_str, p, m->auth_c_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else break;

goto err;

default:

goto err;

}

assert (p == (unsigned char *) src + srclen);

if (type == MUNGE_MSG_HDR) {

if (magic != MUNGE_MSG_MAGIC) {

m_msg_set_err (m, EMUNGE_SOCKET,

strdupf ("Received invalid message magic %d", magic));

return (EMUNGE_SOCKET);

}

else if (version != MUNGE_MSG_VERSION) {

m_msg_set_err (m, EMUNGE_SOCKET,

strdupf ("Received invalid message version %d", version));

return (EMUNGE_SOCKET);

}

}

return (EMUNGE_SUCCESS);

err:

m_msg_set_err (m, EMUNGE_SNAFU,

strdupf ("Failed to unpack message type %d", type));

return (EMUNGE_SNAFU);

nomem:

m_msg_set_err (m, EMUNGE_NO_MEMORY, NULL);

return (EMUNGE_NO_MEMORY);

}

Generally speaking, a message in Munge is made up of both fields of fixed size and field of variable size. The message unpacking is done by reading through the received buffer. For fixed-size fields, the value is simply read and copied into the struct member:

if (!_unpack (&(m->error_num), &p, sizeof (m->error_num), q));

For variable length fields such as tokens data in encoding request the parsing is a bit more complex. It starts by reading the length of the variable size field. Then it allocates a buffer of the corresponding size and copy this number of bytes to the fresh buffer.

else if (!_unpack (&(m->data_len), &p, sizeof (m->data_len), q)) ;

else if (!_alloc (&(m->data), m->data_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->data, p, m->data_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

All variable-size field used this approach except one, m->addr:

else if (!_unpack (&(m->addr_len), &p, sizeof (m->addr_len), q)) ;

else if ( _copy (&(m->addr), p, m->addr_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

This is done that way because m->addr is not a pointer to a struct, but the struct in_addr itself. However, m->addr_len is defined as a uint8_t. The length of struct in_addr is 4 bytes for IPv4. In the case where m->addr_len == 0xff, the copy will overflow out of the struct in_addr into the rest of the struct m_msg and after. This occurs when unpacking messages type of MUNGE_MSG_DEC_RSP, e.g. decoding responses.

file: src/libcommon/m_msg.h

struct m_msg {

int sd; /* munge socket descriptor */

uint8_t type; /* enum m_msg_type */

uint8_t retry; /* retry count for this transaction */

uint32_t pkt_len; /* length of msg pkt mem allocation */

void *pkt; /* ptr to msg for xfer over socket */

uint8_t cipher; /* munge_cipher_t enum */

uint8_t mac; /* munge_mac_t enum */

uint8_t zip; /* munge_zip_t enum */

uint8_t realm_len; /* length of realm string with NUL */

char *realm_str; /* security realm string with NUL */

uint32_t ttl; /* time-to-live */

uint8_t addr_len; /* length of IP address */

struct in_addr addr; /* IP addr where cred was encoded <=== Overflow here. */

uint32_t time0; /* time at which cred was encoded */

uint32_t time1; /* time at which cred was decoded */

uint32_t client_uid; /* UID of connecting client process */

uint32_t client_gid; /* GID of connecting client process */

uint32_t cred_uid; /* UID of client that requested cred */

uint32_t cred_gid; /* GID of client that requested cred */

uint32_t auth_uid; /* UID of client allowed to decode */

uint32_t auth_gid; /* GID of client allowed to decode */

uint32_t data_len; /* length of data */

void *data; /* ptr to data munged into cred */

uint32_t auth_s_len; /* length of auth srvr string w/ NUL */

char *auth_s_str; /* auth srvr path name string w/ NUL */

uint32_t auth_c_len; /* length of auth clnt string w/ NUL */

char *auth_c_str; /* auth clnt dir name string w/ NUL */

uint8_t error_num; /* munge_err_t for encode/decode op */

uint8_t error_len; /* length of err msg str with NUL */

char *error_str; /* descriptive err msg str with NUL */

unsigned pkt_is_copy:1; /* true if mem for pkt is a copy */

unsigned realm_is_copy:1; /* true if mem for realm is a copy */

unsigned data_is_copy:1; /* true if mem for data is a copy */

unsigned error_is_copy:1; /* true if mem for err str is a copy */

unsigned auth_s_is_copy:1;/* true if mem for auth srvr is copy */

unsigned auth_c_is_copy:1;/* true if mem for auth clnt is copy */

};

This vulnerability causes a crash during m_msg_destroy when attempting to free an invalid pointer like error_str.

Exploiting the vulnerability

Since it would take too much time to get a working exploit on our client's actively used High Performance Computer, it was decided to write an exploit for our own lab instead.

Exploitation Context

This exploit is designed for Munge version 0.5.17 compiled with openssl and without debug mechanisms.

munge --version

munge-0.5.17 (2025-11-12)

checksec gives the following output.

●❯ checksec file /usr/bin/munged

_____ _ _ ______ _____ _ __ _____ ______ _____

/ ____| | | | ____/ ____| |/ // ____| ____/ ____|

| | | |__| | |__ | | | ' /| (___ | |__ | |

| | | __ | __|| | | < \___ \| __|| |

| |____| | | | |___| |____| . \ ____) | |___| |____

\_____|_| |_|______\_____|_|\_\_____/|______\_____|

RELRO Stack Canary CFI NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH Symbols FORTIFY Fortified Fortifiable Name

Full RELRO Canary Found SHSTK & IBT NX enabled PIE Enabled No RPATH No RUNPATH No Symbols Yes 6 8 /usr/bin/munged

As you might already know another important information when exploiting heap buffer overflow is the libc version. Here we are targeting glibc version 2.42. This version uses ptmalloc with safe linking. This document will not details the quirks of ptmalloc but only explain the mechanisms in use here.

Step 1 - Breaking ASLR

Due to ASLR, internal addresses (stack, heap, text...) are randomized and will change at every run. The first step of this exploit is to get a leak of those internal addresses. The strategy to get this leak, is to use the buffer overflow to partially overwrite a pointer that will be freed, in order to poison the tcache with fake chunks.

tcacheare per-thread caches of free chunk. When a thread frees a chunk it places it in the tcache. Subsequent malloc will first look in the tcache for a fitting free chunk before going through the entire malloc logic.

Creating a fake free chunk for Data Buffer

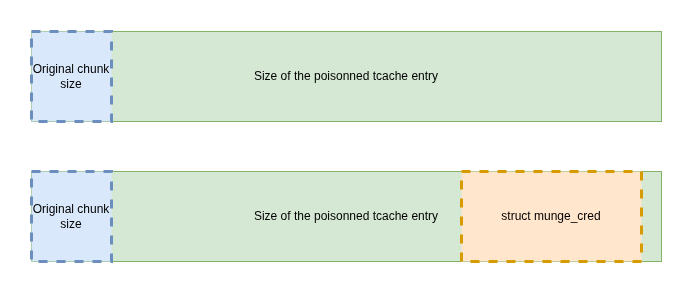

Because we do not know internal addresses, we spray the heap with fake chunk metadata. For an in-use chunk of size 0x10, the metadata stored right before the beginning of the chunk will look like the following:

0x0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 <= Irrelevant

0x8: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 21 <= Size of the chunk + Size of metadata (0x10) + FLAG IN_USE (1)

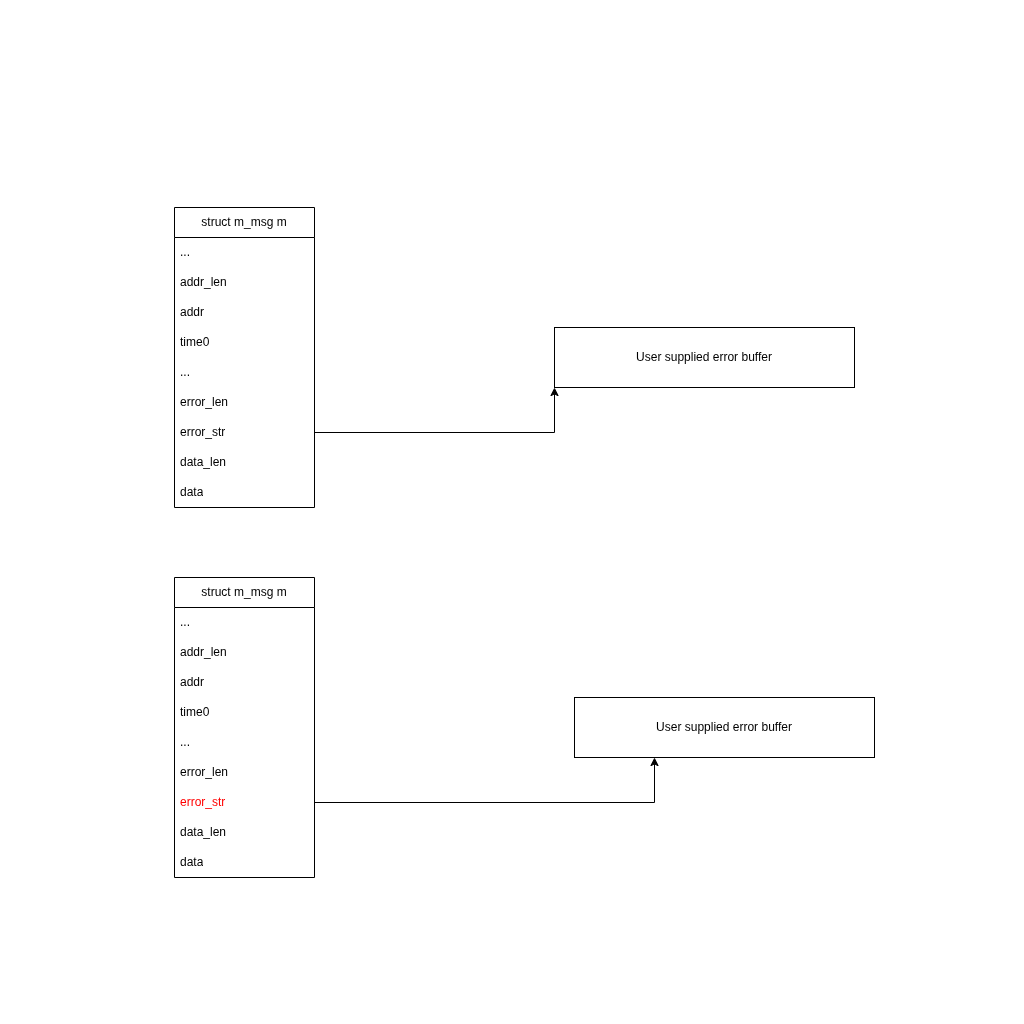

Then we partially overwrite an already set pointer, in our case m->error_str using the Heap Buffer Overflow. Because m->error_str is pointing to data stored on the heap, overwriting least significant bits make it point to somewhere around the same area.

m->error_str, chunk metadata are now attacker suppliedThis allows us to create a fake free chunk of a size we control. This chunk is placed in the tcache of the current thread. (We will get to the multithread scenario later.)

We use this technique to create a chunk of size 0x3e0 in the heap and places it in tcache.

Any subsequent malloc of size 0x3e0, will return this chunk. The message parsing mechanism allows user to sends data of arbitrary size, up to a certain limit, as long as they specify the correct length of the data in the message.

Thus, if after this step, the user send an encoding request containing 0x3e0 bytes of data, malloc will return the pointer to the fake free chunk.

file: src/libcommon/m_msg.c

case MUNGE_MSG_ENC_REQ:

if (!_unpack (&(m->cipher), &p, sizeof (m->cipher), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->mac), &p, sizeof (m->mac), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->zip), &p, sizeof (m->zip), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->realm_len), &p, sizeof (m->realm_len), q));

else if (!_alloc ((vpp) &(m->realm_str), m->realm_len)) goto nomem;

else if ( _copy (m->realm_str, p, m->realm_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->ttl), &p, sizeof (m->ttl), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->auth_uid), &p, sizeof (m->auth_uid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->auth_gid), &p, sizeof (m->auth_gid), q)) ;

else if (!_unpack (&(m->data_len), &p, sizeof (m->data_len), q)) ; # Unpacking user provided m->data_len

else if (!_alloc (&(m->data), m->data_len)) goto nomem; # malloc(m->data_len), here malloc returns the fake chunk

else if ( _copy (m->data, p, m->data_len, p, q, &p) < 0) ; # Copy user provided data into the fake chunk

else break;

goto err;

Struct munge_cred allocated within the data buffer

Now that the first overflow is done, it is possible to simply ask munged to encode new credentials. By sending an encoding request with data of size 0x3e0, the m->data buffer will be the fake freed chunk. After computing the HMAC, munged will return the user provided data in the crafted token.

As this chunk is fake, its size is not consistent with the rest of the heap. ptmalloc does not consider this whole buffer as being in use. This lead to multiple allocations taking place within our data buffer after the function _msg_unpack copied the user provided data.

One of these allocations is the struct munge_cred allocated during enc_process_msg in the cred_create function.

file: src/munged/enc.c

int

enc_process_msg (m_msg_t m)

{

munge_cred_t c = NULL; /* aux data for processing this cred */

int rc = -1; /* return code */

if (enc_validate_msg (m) < 0)

;

else if (!(c = cred_create (m)))

;

else if (enc_init (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_authenticate (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_check_retry (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_timestamp (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_pack_outer (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_pack_inner (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_compress (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_mac (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_encrypt (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_armor (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_fini (c) < 0)

;

else /* success */

rc = 0;

/* Since the same m_msg struct is used for both the request and response,

* the response message data must be sanitized for most errors.

*/

if (rc != 0) {

m_msg_reset (m);

}

if (m_msg_send (m, MUNGE_MSG_ENC_RSP, 0) != EMUNGE_SUCCESS) {

rc = -1;

}

cred_destroy (c);

return (rc);

}

m->dataAs this structure is allocated inside the data buffer before the token encoding occurs, the munge token returned to the user contains the struct in its data part. By simply base64 decoding the returned token, it is possible to leak the content of the cred structure.

Multithread strategy

Tcache is managed per thread. Each running thread as it own list of free bins. As we poison tcache with fake chunks, for the exploit to be consistent we need to be able to target a thread. To do so, the idea is to stall every thread but one by sending partial packets. Workers threads will wait for the rest of data before timing-out after 1 second. As long as the threads are waiting for a complete message they cannot process other incoming packets. We can start our exploit by stalling every worker but one, before sending our actual overflow payload to the remaining thread.

Breaking ASLR

The lead_cred_struct.py is a demonstration of this technic being used to leak ASLR.

$ python leak_cred_struct.py -S /tmp/munged_socket -n 2

[*] Stealing the thread(s)

[*] Init tcache for size 0x30

[+] Initalised

[*] Sending first overflow packet

[*] Shaping the heap part 1,

-> changing chunk size to make sure munge_cred_t is allocated after data

[*] Shaping the heap part 2,

-> changing chunk size to make sure data is placed before credz

[+] Ask for credz to be encoded, leaking cred struct placed in data

[+] Found Struct beginning

cred {

version : 3

msg : 0xe117864ffc0

outer_mem_len : 149

outer_mem : 0xe117864fe40

outer_len : 149

outer : 0xe117864fe40

inner_mem_len : 1033

inner_mem : 0x6ba428003930

inner_len : 1033

inner : 0x6ba428003930

realm_mem_len : 0

realm_mem : NULL

salt_len : 8

salt : 29 c7 2e 0f 05 ce 86 e3 (len=8)

mac_len : 0

mac : 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 (len=64)

dek_len : 0

dek : 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 (len=64)

iv_len : 0

iv : 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 (len=16)

outer_zip_ref : 0xe117864fe43

}

It is interesting to note that we can see two completely different addresses for inner and msg because each thread as its own heap memory zone (arena). The struct m_msg *msg representing the message is allocated by the main thread, while inner is allocated by the worker thread. outer is also allocated by the worker thread, but it reuses a chunk malloc-ed by the main thread, freed in the worker thread, thus placed in its tcache.

Tcache of a thread can contain chunks of other threads arena

Step 2 - Getting mac key

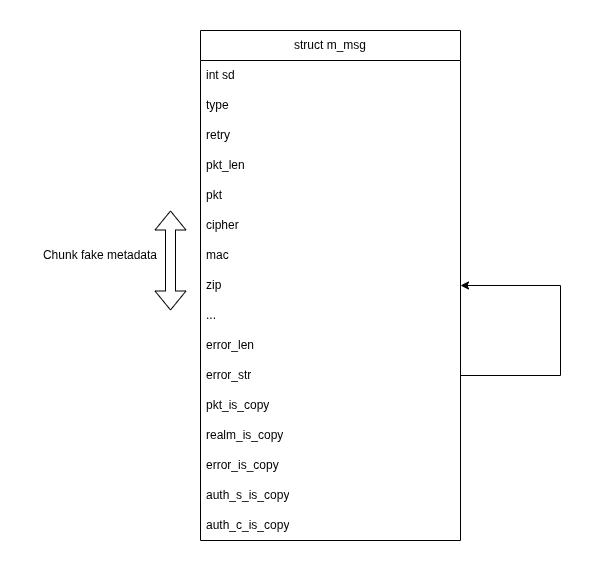

After leaking addresses of the main arena, it is possible to accurately craft a fake chunk right before the zone where m_msg struct are allocated. To do so, instead of a partial overwrite of the error_str pointer, it is overwritten completely and points to the computed address of the current m_msg. The current struct m_msg, holds user provided data, copied during the unpacking. file: src/libcommon/m_msg.h

struct m_msg {

int sd; /* munge socket descriptor */

uint8_t type; /* enum m_msg_type */

uint8_t retry; /* retry count for this transaction */

uint32_t pkt_len; /* length of msg pkt mem allocation */

void *pkt; /* ptr to msg for xfer over socket */

uint8_t cipher; /* munge_cipher_t enum */ # Cipher and mac can store our fake chunk metadata

uint8_t mac; /* munge_mac_t enum */

uint8_t zip; /* munge_zip_t enum */

uint8_t realm_len; /* length of realm string with NUL */

char *realm_str; /* security realm string with NUL */

uint32_t ttl; /* time-to-live */

uint8_t addr_len; /* length of IP address */

struct in_addr addr; /* IP addr where cred was encoded */

...

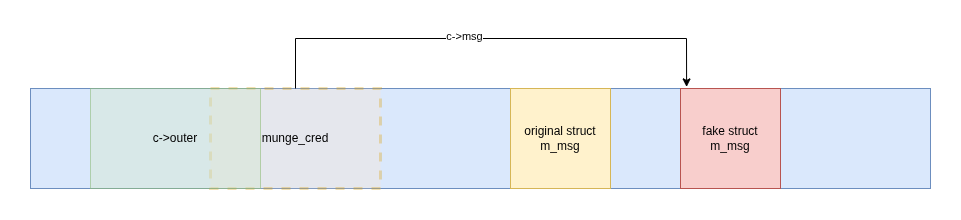

Using this primitive, attacker can completely shape the heap, and populate tcache of multiple size. The heap is then shaped as follows:

- Create a big chunk to hold future msg->data

- Create a smaller chunk for future cred->outer

- Create a bigger chunk for future cred

The idea is that m->data is big enough to overwrite the current struct m_msg being processed. It means that enc_process_msg is called with a m_msg struct, entirely controlled by the attacker. In this overwritten struct m_msg being processed, the data member is pointing to an arbitrary address defined by the attacker.

After validating the struct m_msg, enc_process_msg starts by allocating a struct munge_cred, then copy the address of the current message to the msg member of the cred struct.

Later in the enc_process_msg, during the function enc_pack_outer, the realm part of the token will be copied from the message, to outer buffer. outer is allocated on the heap right before the cred struct. Because it is a fake chunk with fake size it overlaps the credential struct, meaning that, at this point, the attacker gains control over the cred struct. This allows the attacker to replace the pointer to current message by a pointer to a fake struct msg.

Every subsequent calls in enc_process_message will use a fake msg struct. For example, enc_fini, at the end is responsible for replacing c->msg->data by cred->outer which at this point contains the entire base64 encoded data.

All these functions will work on a fake msg struct. However the original message struct is used to respond to the client through m_send_msg. Because msg->data has not been replaced in the original struct m_msg, the m_msg_send will directly send msg->data_len bytes of msg->data to msg->sd file descriptor.

All these values msg->data_len and msg->data are controlled by the attacker thanks to the overflow.

file: src/munged/enc.c

int

enc_process_msg (m_msg_t m) // Here the attacker controls the entire struct

{

munge_cred_t c = NULL;

int rc = -1;

if (enc_validate_msg (m) < 0)

;

else if (!(c = cred_create (m))) // munge_cred struct is created

;

else if (enc_init (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_authenticate (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_check_retry (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_timestamp (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_pack_outer (c) < 0) // munge_cred is overwritten with user controlled data, c->msg point to a fake struct

;

else if (enc_pack_inner (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_compress (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_mac (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_encrypt (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_armor (c) < 0)

;

else if (enc_fini (c) < 0)

;

else /* success */

rc = 0;

if (rc != 0) {

m_msg_reset (m);

}

if (m_msg_send (m, MUNGE_MSG_ENC_RSP, 0) != EMUNGE_SUCCESS) { // m->data is sent to the attacker

rc = -1;

}

cred_destroy (c);

return (rc);

}

At this point the attacker is able to receive arbitrary amount of data, from arbitrary addresses. This is used to leak several pages of the heap. Hoping these pages contains the mac key.

Step 3 - Finding the key

The first token received by the attacker to leak the credentials structure, is a valid token, with valid HMAC, despite having leaked data. To find the key amongst the multiple pages of received data, a naive approach is to try every possible keys within these data to recompute the HMAC. If the HMAC is valid, the key is correct. The decoding logic is located in decode.py Same logic can be applied to find the encryption key.

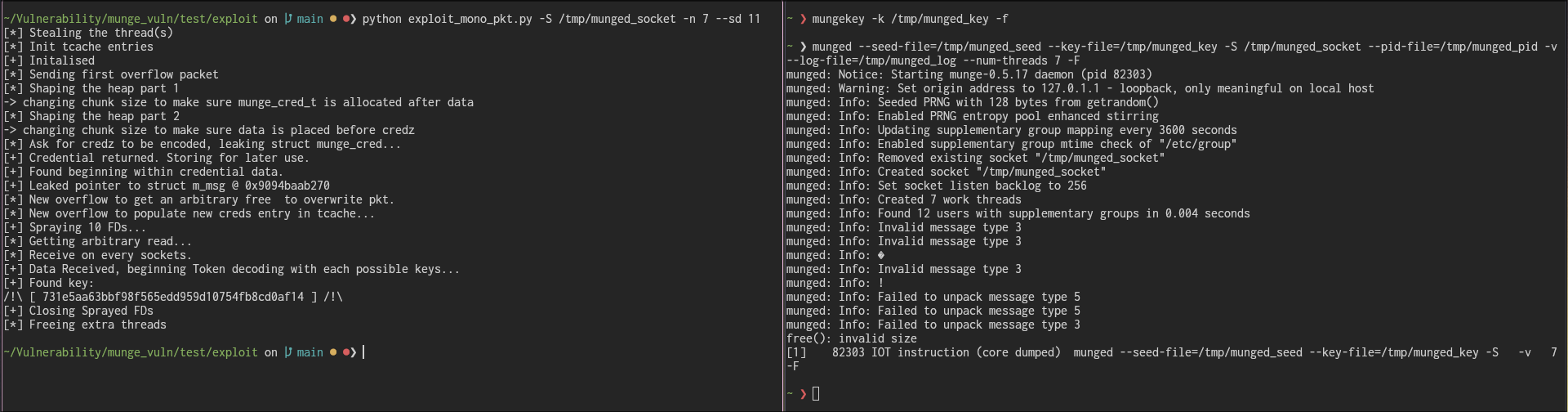

Full exploit

The code of the exploit can be found here

hmac key, which can be used to forge new arbitrary token as any other usersFuture Work

Some work can still be done to improve the exploit.

Exploit Stability: The most important one, this exploit only works on a freshly created server, with a clean heap. Making it work on an active server will require a lot of work, more than what Lexfo is willing to put on an already patched vulnerability. It could also be interesting to prevent the server from crashing after the exploit, by restoring the heap into a non-buggy state. This will be particularly difficult.

Gaining code execution: The current exploit only leaks the private key. It is always funnier to gain code execution. In most configuration gaining code execution is completely useless as Munged run as Munge user and is only able to read the munge private key and create the UNIX socket. More importantly, Munge token can be used to impersonate high privileges user on other nodes.

Exploiting Munge Client: Gaining code execution on the munge server could also be used to gain code execution on clients. The vulnerability relies in the libcommon imported by both the servers and clients. It must be possible to exploit the same vulnerability on clients by sending the messages from the server to the clients.

Disclosure Timeline & Acknowledgements

- [2026/01/12]: The vulnerability is discovered

- [2026/01/13]: We started to work on a proof of concept

- [2026/01/26]: The vulnerability is reported to Chris Dunlap the Munge maintainer

- [2026/01/29]: Chris sent us the fix for review

- [2026/02/01]: CVE-2026-25506 was assigned

- [2026/02/10]: Patch is published

Nicolas FABRETTI from Lexfo helped on this research. His suggestion to fuzz munge using AFL, as well as his technical assistance lead to the discovery of this buffer overflow.

Chris DUNLAP has been very reactive and professional during this disclosure. He has been able to produce fixes very quickly for the security bugs we reported, and showed interest on the exploitation part too. Munge is another example of key component used by major companies being maintained by a single developer for more than 20 years. He handled the process of reporting the vulnerability to Linux distributions.

And finally, we can thank the customer who asked for the security audit of its HPC infrastructure, thus giving us a particularly interesting mission.

Conclusion

This major vulnerability was found during what was supposed to be a standard infrastructure audit. Sometime pentesting is more than web server and active directories. As pentesters, writing Heap buffer overflow exploit is not our day-to-day job and it was a great opportunity to skill up.