Introduction

During a Red Team, we stumbled upon a device running Android. Next to the battery slot, a pin header providing access to a debug UART and an USB port were present. After improvising a custom USB cable by crimping bullet terminals since we didn't have access to a soldering iron, we gained access to the device through MTP:

| 8-pin connector | A mouse had to be sacrificed |

|---|---|

|  |

Using MTP, we could retrieve a configuration file containing only ASCII characters, however they didn't make sense. Best guess we had was it could be some Base64 with a custom charset randomly selected.

Since we supposed these configuration files would only be obfuscated, we wanted to reverse engineer the application that can read them. Based on the name of a service displayed on the device, we knew what to search for on Google Play to find an APK that would use, and thus decode, such configuration files. As a matter of fact, the application is a Mobile Device Management.

Obviously, the APK was all obfuscated. We quickly found the Java interface used for the decoding of the configuration:

public interface AbstractC3001 {

/* renamed from: ı */

String mo20891(String str) throws MissingDataForEncryptionException;

}

However, no implementation of this interface could be found in what we had. Obviously, the implementation must have been encrypted and dynamically loaded at runtime.

Decompiling the APK

First, we need to decompile the APK. Jadx can work quite well to get some Java-esque output. Getting the smali for reference with Apktool is also a good idea.

$ jadx --show-bad-code --deobf -d out/ target.apk

$ apktool d target.apk

One of the packages is heavily obfuscated in the application. In our case it is named p014o. The use of Dexguard can be recognized with its Class Manager (CM) that resolves class and method names at runtime. The prototype for the CM is basically String $$c(arg1, arg2, arg3). We can find it easily:

$ grep -r 'private static String $$c(' out/sources/

out/sources/p014o/C2958.java: private static String $$c(int r7, short r8, short r9) {

Now we need to find "strange" resources. Two resources at the root of the application folder have non-printable names that end in '-'. They also start with a Java reference and are followed by a high-entropy blob of data.

$ ls out/resources/*-

out/resources/ -

'out/resources/'$'\342\200\251'' '$'\342\200\251''-'

$ strings -n 10 out/resources/*-

java/io/Serializable

java/io/Serializable-

These resources are actually encrypted with custom versions of well-known cryptographic algorithms. One will be the Class Loader (CL), and the other one the Protected Classes. In order to decrypt the Protected Classes (PC), we first need to decrypt the Class Loader which will contain the key and some parameters for the Protected Classes decryption.

In the CM (in our case: out/sources/p014o/C2958.java), there is a huge static initialization. This is where the Protected Classes will be decrypted and then loaded.

Last time we checked, the Dexguard mode of operation was:

- load a resource as an InputStream;

- feed the result to a class inheriting from FilterInputStream to decrypt it;

- do some useless obfuscation to waste a few minutes of time from a reverser;

- feed the decrypted result to a ZipInputStream to get a DEX file;

- finally load the resulting DEX as a Resource using the

loadDexmethod.

So let's find what classes extend FilterInputStream using grep:

$ grep -r 'extends FilterInputStream' out/sources/p014o/

out/sources/p014o/C1538.java:public class C1538 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C1489.java:public final class C1489 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C2081.java:public final class C2081 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C1207.java:public final class C1207 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C0991.java:public final class C0991 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C1742.java:public final class C1742 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C1209.java:public final class C1209 extends FilterInputStream {

out/sources/p014o/C4315CoN.java:public final class C4315CoN extends FilterInputStream {

The class in C1207 strongly resembles some fast AES implementation, as can be seen from its dependency C1210 with a static initializer computing AES lookup tables:

static {

byte[] bArr;

int i;

byte b = 1;

byte b2 = 1;

do {

b = (byte) (((b & 128) != 0 ? 27 : 0) ^ ((b << 1) ^ b));

byte b3 = (byte) (b2 ^ (b2 << 1));

byte b4 = (byte) (b3 ^ (b3 << 2));

byte b5 = (byte) (b4 ^ (b4 << 4));

b2 = (byte) (b5 ^ ((b5 & 128) != 0 ? (byte) 9 : 0));

bArr = f1476;

i = b & 255;

int i2 = b2 & 255;

bArr[i] = (byte) (((((b2 ^ 99) ^ ((i2 << 1) | (i2 >> 7))) ^ ((i2 << 2) | (i2 >> 6))) ^ ((i2 << 3) | (i2 >> 5))) ^ ((i2 >> 4) | (i2 << 4)));

} while (i != 1);

bArr[0] = 99;

for (int i3 = 0; i3 < 256; i3++) {

int i4 = f1476[i3] & 255;

f1471[i4] = (byte) i3;

int i5 = i3 << 1;

if (i5 >= 256) {

i5 ^= 283;

}

int i6 = i5 << 1;

if (i6 >= 256) {

i6 ^= 283;

}

int i7 = i6 << 1;

if (i7 >= 256) {

i7 ^= 283;

}

int i8 = i7 ^ i3;

int i9 = ((i5 ^ (i6 ^ i7)) << 24) | (i8 << 16) | ((i8 ^ i6) << 8) | (i8 ^ i5);

f1475[i4] = i9;

f1470[i4] = (i9 >>> 8) | (i9 << 24);

f1472[i4] = (i9 >>> 16) | (i9 << 16);

f1474[i4] = (i9 << 8) | (i9 >>> 24);

}

f1473[0] = 16777216;

int i10 = 1;

for (int i11 = 1; i11 < 10; i11++) {

i10 <<= 1;

if (i10 >= 256) {

i10 ^= 283;

}

f1473[i11] = i10 << 24;

}

}

The class C1209 looks like a broken stream cipher loosely based on Mersenne twisters with 64-bits word size and two 4-words internal states, as can be deduced from its dependency class C1208:

public final class C1208 {

/* renamed from: ι */

static long[] m1400(int i, int i2) {

long[] jArr = new long[4];

jArr[0] = (((long) i2) & 4294967295L) | ((((long) i) & 4294967295L) << 32);

for (int i3 = 1; i3 < 4; i3++) {

long j = jArr[i3 - 1];

jArr[i3] = ((j ^ (j >> 30)) * 1812433253) + ((long) i3);

}

return jArr;

}

}

In the past, we also found TEA, XTEA and Blowfish.

Because the encryption algorithm implemented in C1209 is severely broken, we could directly guess the missing bits of key that are present in the Class Loader and decrypt the Protected Classes. However, in some cases it is still necessary to decrypt the Class Loader to retrieve them. In order to cover all the cases we will do like if we couldn't directly decrypt the Protected Classes with the information we already have.

Decrypting the Class Loader

In order to decrypt the Class Loader, we have to find a reference to one of the two decryption algorithms implemented in C1209 and C1207. By looking into the CM (class C2958), we can find a call to the C1207 constructor:

byte[] bArr3 = new byte[16];

bArr3[0] = -29;

bArr3[1] = -87;

bArr3[2] = -61;

bArr3[3] = 81;

bArr3[4] = -30;

bArr3[5] = -71;

bArr3[6] = -19;

bArr3[7] = -31;

bArr3[8] = 123;

bArr3[9] = -74;

bArr3[10] = 119;

bArr3[11] = -37;

bArr3[12] = -12;

try {

bArr3[13] = -75;

bArr3[14] = 65;

bArr3[15] = -104;

byte[] bArr4 = (byte[]) bArr3.clone();

C1203.m1385(bArr4, f5121, f5116);

inputStream = new C1207(inputStream2, 8, bArr4, C1210.m1404(518096760));

The first argument is an InputStream, we will take a look at it later. The second is actually the number of rounds, 8 instead of 10 for AES128; the third argument is the key, notice that it is modified by a call to C1203.m1385(). Finally, the last argument is the ShiftRow matrix that is obviously different than the one in normal AES. It is generated through a call to C1210.m1404(). The actual prototype would look like that:

public C1207(InputStream inputStream, int numRound, byte[] aesKey, byte[][] shiftRowMatrix);

AES Key

The key can be easily identified in the code snippet above. Although, we need to take a look at C1203.m1385 to see how it is actually modified before it is used:

/* renamed from: o.ĸӀ */

public class C1203 {

/* renamed from: ɩ */

public static void m1385(byte[] bArr, byte b, long j) {

for (int i = 0; i < bArr.length; i++) {

if (((1 << i) & j) != 0) {

bArr[i] = (byte) (bArr[i] ^ b);

}

}

}

}

As we can see, a XOR operation with f5121 is applied for bytes whose index matches a bit set to 1 in f5116, LSB first.

private static long f5116 = 2459692291946227616L;

/* ... */

private static byte f5121 = -89;

We can obtain the final key using a small C code:

static uint8_t key[] = { -29, -87, -61, 81, -30, -71, -19, -31, 123, -74, 119, -37, -12, -75, 65, -104 };

uint8_t *modif_key(uint8_t* ikey, uint8_t m, uint64_t mask, size_t len)

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < len; i++) {

if (((1 << i) & mask) != 0) {

ikey[i] ^= m;

}

}

return ikey;

}

The result is:

Before: E3A9C351E2B9EDE17BB677DBF4B54198

After: E3A9C351E21EED46DC11D0DBF412413F

AES Shift Row matrix

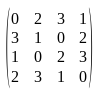

Next, we need to compute the actual shift row matrix used. Normally the Shift Row operation for AES decryption uses this matrix:

Let's take a look at C1210.m1404:

/* renamed from: ɩ */

public static byte[][] m1404(int i) {

byte[][] bArr = new byte[4][];

for (int i2 = 0; i2 < 4; i2++) {

int i3 = i >>> (i2 << 3);

bArr[i2] = new byte[]{(byte) (i3 & 3), (byte) ((i3 >> 2) & 3), (byte) ((i3 >> 4) & 3), (byte) ((i3 >> 6) & 3)};

}

return bArr;

}

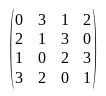

It is called with 518096760, converting to base-4 (0132320120131320) and rearranging as done in the snippet above would give the following matrix:

Now let's take a look at the C1207 constructor. Although useless, there is another transformation applied to this matrix. This is useless because if we want to make things quick, based on what we already have we can simply compile the C1207 class with javac and call it with the arguments we already have computed. So, it doesn't add any value to the obfuscation. Anyway, here is the final transformation:

/* renamed from: ι */

private static byte[][] m1399(byte[][] bArr) {

byte[][] bArr2 = new byte[bArr.length][];

for (int i = 0; i < bArr.length; i++) {

bArr2[i] = new byte[bArr[i].length];

for (int i2 = 0; i2 < bArr[i].length; i2++) {

bArr2[i][bArr[i][i2]] = (byte) i2;

}

}

return bArr2;

}

For each row, the cell values and their indices are exchanged, giving the final Shift Row matrix used:

Input Stream

We now have the algorithm to decrypt the Class Loader, which is a modified AES128 with 8-rounds and a custom Shift Row matrix, as well as the decryption key. We also know that the encrypted Class Loader is one of the two resource files with non-printable characters in their names.

If we backtrack the InputStream argument, we obtain it after this call:

i6 = 20;

/* ... */

int length4 = bArr.length;

int i90 = -i6;

int i91 = (length4 & i90) + (length4 | i90);

/* ... */

Object[] objArr22 = new Object[3];

objArr22[2] = Integer.valueOf(i91);

objArr22[1] = Integer.valueOf(i6);

objArr22[0] = bArr;

short s30 = (short) 135;

InputStream inputStream2 = (InputStream) Class.forName($$c((byte) f5118[35], s30, (short) ((s30 ^ 376) | (s30 & 376)))).getDeclaredConstructor(byte[].class, Integer.TYPE, Integer.TYPE).newInstance(objArr22);

Note that the formula (a & b) + (a | b) is equivalent to a + b. While we could decrypt the class name by reimplementing the $$c method, it seems quite obvious that the constructor is simply:

ByteArrayInputStream(byte[] buf, int offset, int length);

The offset is 20 and the length is the whole buffer length minus 20. Since the resources we found started with java/io/Serializable which is 20 bytes long, it actually makes sense.

We need to take a look at what operation is done to bArr before being used in the ByteArrayInputStream constructor. We have this code snippet above in the code:

i6 = 20;

i7 = 8664;

str3 = str2;

cls = null;

while (true) {

int i89 = ((i6 | 210) << 1) - (i6 ^ 210);

try {

byte b19 = bArr[((i6 | 4167) << 1) - (i6 ^ 4167)];

bArr[i89] = (byte) ((b19 ^ 9) + ((b19 & 9) << 1));

Note that the formulae ((a | b) << 1) - (a ^ b) and (a ^ b) + ((a & b) << 1) are equivalent to a + b. The code above can be reduced to:

bArr[20 + 210] = bArr[20 + 4167] + 9;

Getting the Class Loader Dex

The resource files were 8708 and 4188 bytes long respectively. Since AES works on 16-bytes blocks, the best candidate is thus the file whose length is 8708 since it is 243 * 16 + 20.

By replacing the 230th byte by the 4187th added with 9 (which gives 0x4 + 0x9 = 0x0d), we can finally decrypt the CL using the key 0xE3A9C351E21EED46DC11D0DBF412413F with a slightly modified version of the AES implementation to take into account the reduced round number and the custom Shift Row matrix. A diff based on the reference implementation of AES can be found in the annex.

The decryption can be obtained using this C code, for example:

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int fd, outfd, i;

uint8_t buf[20], obuf[16];

uint32_t keyexp[4*9];

fd = open(argv[1], O_RDONLY);

read(fd, buf, 20);

outfd = open(argv[2], O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, S_IRUSR | S_IWUSR);

modif_key(key, -89, 2459692291946227616ULL, 16);

m1404(518096760);

m1399();

rijndaelKeySetupDec(keyexp, 8, key, 128);

while (read(fd, buf, 16) == 16) {

rijndaelDecrypt(keyexp, 8, buf, obuf);

write(outfd, obuf, 16);

}

close(outfd);

}

We can now obtain the JAR file in plaintext:

$ gcc -o main main.c rijndael-alg-fst.c

$ ./main encfile1 cl.jar

KEY: E3A9C351E21EED46DC11D0DBF412413F

ShifRow Matrix:

0, 3, 1, 2,

2, 1, 3, 0,

1, 0, 2, 3,

3, 2, 0, 1,

And finally get the Dex file:

$ unzip cl.jar

Archive: cl.jar

warning [cl.jar]: 22 extra bytes at beginning or within zip file

(attempting to process anyway)

inflating: classes.dex

Decrypting the Protected Classes

We can now feed this classes.dex to Jadx along with the one from the APK we are analyzing so that both are integrated:

$ mv classes.dex classes2.dex

$ unzip target.apk classes.dex

Archive: target.apk

inflating: classes.dex

$ jadx --show-bad-code --deobf -d cl/ classes*.dex

INFO - loading ...

INFO - processing ...

ERROR - finished with errors, count: 26

We now have the Class Loader decompiled with the renaming matching the other decompiled classes, thanks to Jadx. The classes have now all be renamed because of the deobfuscation flag given to Jadx. The Class Manager, formerly C2958 is now named C2274. The second decryption class identified, C1209 is now named C1081. The newly obtained Class Loader is named C2257.

Identifying the Class Loader call to decrypt the Protected Classes

If we go back to the Class Manager (now renamed C2274), there is one use of an InputStream object that we didn't investigate:

clsArr7[0] = Class.forName($$c(b20, s31, (short) ((i94 & 415) | (i94 ^ 415))));

clsArr7[1] = Short.TYPE;

clsArr7[2] = Integer.TYPE;

clsArr7[3] = Integer.TYPE;

inputStream = (InputStream) cls6.getMethod($$c8, clsArr7).invoke(obj25, objArr23);

The argument objArr23 can be found some few lines above:

Object[] objArr23 = new Object[4];

objArr23[3] = -1541368241;

objArr23[2] = -197155059;

objArr23[1] = (short) 8;

objArr23[0] = inputStream2;

This means the method signature looks like this:

InputStream method(InputStream, short, int, int);

If we take a look at the Class Loader we just decrypted (named C2257 in our case), only one method has this specific signature. Looking for InputStream gives us this code snippet:

/* renamed from: ǃ */

public InputStream mo19845(InputStream inputStream, short s, int i, int i2) throws IOException {

try {

try {

C1081 r7 = new C1081(inputStream, this.f3561, i, s, this.f3560, i2);

try {

int i3 = f3551;

int i4 = (i3 ^ 61) + ((i3 & 61) << 1);

try {

f3548 = i4 % 128;

int i5 = i4 % 2;

return r7;

} catch (Exception e) {

throw e;

}

} catch (ClassCastException e2) {

throw e2;

}

} catch (Exception e3) {

throw e3;

}

} catch (IndexOutOfBoundsException e4) {

throw e4;

}

}

We can see the call to the second decryption algorithm, with some interesting arguments:

C1081(inputStream, this.f3561, i, s, this.f3560, i2);

Decryption key

The value we were missing to call C1081 (formerly C1209 that we identified as a cipher loosely based on Mersenne twisters) can now be recovered from the Class Loader C2257:

this.f3560 = -1658185820;

this.f3561 = -1460155994;

As is usual for DexGuard, we had to decrypt the Class Loader in order to find the key to decrypt the Protected Classes. However, note that in this instance, because the second encryption algorithm used is broken, we could have directly guessed those two missing 32-bits values.

The call to the decryption class is then:

C1081(inputStream, -1460155994, -197155059, 8, -1658185820, -1541368241);

Stream cipher

The C1081 constructor uses the 4th argument (8) as a block size. Although, looking at the code it could be used as a stream cipher directly.

The int arguments are transformed through another class during initialization:

this.f1021 = C1080.m1121(i ^ i4, i5 ^ i4);

this.f1022 = C1080.m1121(i2 ^ i4, i3 ^ i4);

This is the seeding method identified at the beginning of this analysis that actually helped understand on what was based this algorithm. The implementation of this method is as follows:

public final class C1080 {

/* renamed from: ι */

static long[] m1121(int i, int i2) {

long[] jArr = new long[4];

jArr[0] = (((long) i2) & 4294967295L) | ((((long) i) & 4294967295L) << 32);

for (int i3 = 1; i3 < 4; i3++) {

long j = jArr[i3 - 1];

jArr[i3] = ((j ^ (j >> 30)) * 1812433253) + ((long) i3);

}

return jArr;

}

}

You might notice the constant 1812433253 which is the value for f used in the 32-bits version of the Mersenne-Twister MT19937. This class actually implements the initialization part of a Mersenne twister with w = 64 and n = 4. Since it is called twice, we have two internal states. One is initialized with 0xcd75fe9a4209647 and the other one is initialized with 0x501f3142390a81eb. Without decrypting the Class Loader, we would only have the lower part of the first initialization and the upper part of the second.

Now let's take a look at the decryption implementation:

long[] jArr = this.f1021;

long[] jArr2 = this.f1022;

short s = this.f1017;

int i = (s + 2) % 4;

int i2 = (s + 3) % 4;

jArr2[i2] = ((jArr[i2] * 2147483085) + jArr2[i]) / 2147483647L;

jArr[i2] = ((jArr[s % 4] * 2147483085) + jArr2[i]) % 2147483647L;

for (int i3 = 0; i3 < this.f1019; i3++) {

byte[] bArr = this.f1018;

bArr[i3] = (byte) ((int) (((long) bArr[i3]) ^ ((this.f1021[this.f1017] >> (i3 << 3)) & 255)));

}

this.f1017 = (short) ((this.f1017 + 1) % 4);

The two MT-like internal states are first updated with one another, then the current 8-byte block from the ciphertext is XOR'd with the current word from the first internal state.

The internal state update puts the integer part of a division by 2^31-1 in the second internal state and the remainder in the first one. Because of that, after the 4th update, we will have a maximum of 31 bits per word in the first internal state and 33 in the second.

Because the operations are done on signed integer, we have to take into account that the remaining upper bits will be either all 0s or all 1s. This means that blocks of ~32 bits are either the same as the cleartext or have all their bits reversed in the resulting ciphertext. This is particularly inefficient.

Moreover, because we know that the plaintext will start with the string java/, we can directly recover the missing upper part of the seed for the first internal state. The remaining missing 32-bits can then be easily bruteforced or computed by guessing the rest of the starting string in the plaintext (based on a dictionary).

Input Stream

As for the Class Loader, a byte in the ciphertext is actually incorrect. The exact same operation is applied with the Protected Class ciphertext, that is, replacing the 230th byte by the 4187th added with 9. Note that it is always the second-to-last byte of the smaller resource that is taken as a reference to modify a byte close to the beginning of the resources.

Note that if we look at the control flow, we should have noticed that the member f3601 from the Class Manager will actually hold the Class Loader. There are checks such as:

if (!(f3601 == null)) {

This is to determine if we are decrypting the Class Loader (when not null) or the Protected Classes.

Getting the Protected Classes Dex

We will need to do the same byte modification before "decrypting". By replacing the 230th byte by the 4187th added with 9 (which gives 0x1 + 0x9 = 0x0a), we can finally decrypt the Protected classes using the "double key" 0xcd75fe9a4209647 0x501f3142390a81eb.

Since the output of Jadx can be directly compiled, we can use the original implementation in Java. We can also quickly reimplement it in C:

int64_t twister1[4];

int64_t twister2[4];

void init(int64_t seed, int64_t *state)

{

int i;

state[0] = seed;

for (i = 1; i < 4; i++) {

state[i] = (0x6c078965 * (state[i - 1] ^ (state[i - 1] >> 30)) + i);

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int idx = 0;

int i, fd, outfd;

uint8_t buf[20];

fd = open(argv[1], O_RDONLY);

read(fd, buf, 20);

outfd = open(argv[2], O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, S_IRUSR | S_IWUSR);

init(0x0cd75fe9a4209647, twister1);

init(0x501f3142390a81eb, twister2);

while (read(fd, buf, 8) == 8) {

twister2[(idx + 3) % 4] = ((twister1[(idx + 3) % 4] * 0x7FFFFDCD) + twister2[(idx + 2) % 4]) / 0x7FFFFFFF;

twister1[(idx + 3) % 4] = ((twister1[(idx + 0) % 4] * 0x7FFFFDCD) + twister2[(idx + 2) % 4]) % 0x7FFFFFFF;

for (i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

buf[i] ^= (twister1[idx] >> (8 * i)) & 0xFF;

}

idx++;

idx %= 4;

write(outfd, buf, 8);

}

close(outfd);

close(fd);

}

Then we can obtain the Dex file:

$ unzip pc.jar

Archive: pc.jar

warning [pc.jar]: 22 extra bytes at beginning or within zip file

(attempting to process anyway)

inflating: classes.dex

Decompiling the whole project

We can now feed this new classes.dex to Jadx along with the one from the APK we are analyzing so that both are integrated:

$ mv cl/classes.dex classes3.dex

$ jadx --show-bad-code --deobf -d project/ classes*.dex

INFO - loading ...

INFO - processing ...

ERROR - finished with errors, count: 26

Note that this time the class name didn't change, since we only added two additional classes with no direct dependency over the rest of the decompilation. We can find the additional classes using diff:

$ diff -rq project/sources/p010o/ cl/sources/p010o/ | grep Only

Only in project/sources/p010o/: C3157.java

Only in project/sources/p010o/: C3158.java

The first class implements an AES encryption with a hardcoded key to communicate with the MDM server, and the second one is used to deobfuscate the configuration files. We indeed found what looks like a base64 decoding using an obfuscated custom charset:

int indexOf = m6296(new char[]{56674, /*[...]*/ 40470}).intern().indexOf(substring2.charAt(i));

if ((indexOf < m6296(new char[]{29383, 11261, 45856, 8033, 10541, 22108, 25214, 30659, 58107, 55254, 14618, 58864, 14018, 44529, 7991, 15470, 19635, 39717, 39670, 16382, 48010, 15556, 55341, 57354, 38037, 11242, 4227, 54049, 48270, 19667, 812, 6934, 28332, 14278, 47363, 20756, 57729, 41508, 31548, 11732, 20431, 31561, 33119, 61383, 24025, 58306, 18241, 30904, 52967, 36982, 32032, 40856, 34637, 20511, 4255, 54644, 53525, 56183, 24255, 22493, 27537, 12587, 31638, 39543, 20593, 21294}).intern().length() ? 'Z' : 'X') != 'X') {

int i4 = f5309 + 111;

f5312 = i4 % 128;

char[] cArr = {29383, 11261, 45856, 8033, 10541, 22108, 25214, 30659, 58107, 55254, 14618, 58864, 14018, 44529, 7991, 15470, 19635, 39717, 39670, 16382, 48010, 15556, 55341, 57354, 38037, 11242, 4227, 54049, 48270, 19667, 812, 6934, 28332, 14278, 47363, 20756, 57729, 41508, 31548, 11732, 20431, 31561, 33119, 61383, 24025, 58306, 18241, 30904, 52967, 36982, 32032, 40856, 34637, 20511, 4255, 54644, 53525, 56183, 24255, 22493, 27537, 12587, 31638, 39543, 20593, 21294};

String obfuscation

Obviously, DexGuard also provides some level of string obfuscation. The class responsible for the deobfuscation is C1107 (formerly C1236 in the original decompilation output):

public final class C1107 {

/* renamed from: ɩ */

public static void m1192(char[] cArr, char c, char c2, char c3, char c4) {

char c5 = 58224;

for (int i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

cArr[1] = (char) (cArr[1] - (((cArr[0] + c5) ^ ((cArr[0] << 4) + c3)) ^ ((cArr[0] >>> 5) + c4)));

cArr[0] = (char) (cArr[0] - (((cArr[1] >>> 5) + c2) ^ ((cArr[1] + c5) ^ ((cArr[1] << 4) + c))));

c5 = (char) (c5 - 40503);

}

}

}

Four wide char are necessary, they change in each class that uses this obfuscation. In our class the values are:

static void m6297() {

f5307 = 34125;

f5310 = 13075;

f5311 = 49843;

f5306 = 58803;

}

The method is invoked with the constant in this order:

C1107.m1192(cArr3, f5306, f5311, f5307, f5310);

The first element gives the string size, since there is some garbage at the end. The deobfuscation can be called directly in java, or reimplemented in another language to decode all obfuscated strings. As a matter of fact, in its latest version, JEB will directly give the decoded string, saving us some precious time.

Originally, we used the following code to deobfuscate the strings:

unsigned short cArr[2];

unsigned char out[256];

int i, str_idx, str_sz;

unsigned short c = 58803, c2 = 49843, c3 = 34125, c4 = 13075;

for(i=0;i<sizeof str;i+=2) {

unsigned short c5 = 58224;

cArr[0] = str[i];

cArr[1] = str[i+1];

for (int i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

cArr[1] = (unsigned short) (cArr[1] - (((cArr[0] + c5) ^ ((cArr[0] << 4) + c3)) ^ ((cArr[0] >> 5) + c4)));

cArr[0] = (unsigned short) (cArr[0] - (((cArr[1] >> 5) + c2) ^ ((cArr[1] + c5) ^ ((cArr[1] << 4) + c))));

c5 = (unsigned short) (c5 - 40503);

}

if (i == 0) {

str_sz = cArr[0];

str_idx = 0;

out[str_idx++] = (unsigned char) cArr[1];

} else if (str_idx < str_sz) {

out[str_idx++] = (unsigned char) cArr[0];

if (str_idx < str_sz) {

out[str_idx++] = (unsigned char) cArr[1];

} else {

out[str_idx++] = 0;

}

} else if (str_idx == str_sz) {

out[str_idx++] = 0;

}

}

printf("%s\n", out);

Which gives the following Java code for the decoding of our configuration files:

int indexOf = "[REDACTED]".indexOf(substring2.charAt(i));;

if(indexOf < "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/=".length()) {

sb.append(((char)"ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/=".charAt(v5)));

}

As we originally guessed, it was indeed a Base64 encoding with a custom charset.

Deobfuscating the configuration file

There is some additional obfuscation after that. The buffer is reversed and each byte is added with a value incremented at each index and reset every 5 characters.

In the end, we obtain some useful credentials to play a bit more with the device:

<user username="admin" password="[REDACTED]" group="ADMIN" />

With these credentials, it is possible to reach the Android configuration and activate ADB, as well as the BlueTooth tethering in order to bounce on an internal network.

Bonus

Once ADB was activated, we could dump a lot of files from the device, such as all the applications installed. From there, finding a command injection run as root is just a matter of time. This is useful to dump the WiFi credentials in order to not depend on the device to bounce on the internal network.

Conclusion

The aim of this blog post was to present a method for reverse engineering Android application protected by DexGuard using opensource tools, in the context of a real-world example. Using JEB can however speed up the process of deobfuscation, but as far as we know, the most "technical" parts must still be made separately to obtain the decrypted DEX files.

While the device in itself seemed innocuous, it ended up being a great way to gain access to a sensitive network. Stacking layers upon layers of obfuscation doesn't help against a motivated attacker.

Annex

Diff between AES reference implementation and DexGuard implementation

diff -ru aes/rijndael-alg-fst.c code/rijndael-alg-fst.c

--- aes/rijndael-alg-fst.c 2000-12-06 22:48:16.000000000 +0100

+++ code/rijndael-alg-fst.c 2022-04-05 15:23:49.400531669 +0200

@@ -725,7 +725,7 @@

*

* @return the number of rounds for the given cipher key size.

*/

-int rijndaelKeySetupEnc(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits) {

+int rijndaelKeySetupEnc(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], int Nr, const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits) {

int i = 0;

u32 temp;

@@ -745,8 +745,8 @@

rk[5] = rk[1] ^ rk[4];

rk[6] = rk[2] ^ rk[5];

rk[7] = rk[3] ^ rk[6];

- if (++i == 10) {

- return 10;

+ if (++i == Nr) {

+ return Nr;

}

rk += 4;

}

@@ -765,8 +765,8 @@

rk[ 7] = rk[ 1] ^ rk[ 6];

rk[ 8] = rk[ 2] ^ rk[ 7];

rk[ 9] = rk[ 3] ^ rk[ 8];

- if (++i == 8) {

- return 12;

+ if (++i == (3 * Nr) >> 2) {

+ return Nr;

}

rk[10] = rk[ 4] ^ rk[ 9];

rk[11] = rk[ 5] ^ rk[10];

@@ -787,8 +787,8 @@

rk[ 9] = rk[ 1] ^ rk[ 8];

rk[10] = rk[ 2] ^ rk[ 9];

rk[11] = rk[ 3] ^ rk[10];

- if (++i == 7) {

- return 14;

+ if (++i == Nr >> 1) {

+ return Nr;

}

temp = rk[11];

rk[12] = rk[ 4] ^

@@ -811,12 +811,12 @@

*

* @return the number of rounds for the given cipher key size.

*/

-int rijndaelKeySetupDec(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits) {

- int Nr, i, j;

+int rijndaelKeySetupDec(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], int Nr, const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits) {

+ int i, j;

u32 temp;

/* expand the cipher key: */

- Nr = rijndaelKeySetupEnc(rk, cipherKey, keyBits);

+ rijndaelKeySetupEnc(rk, Nr, cipherKey, keyBits);

/* invert the order of the round keys: */

for (i = 0, j = 4*Nr; i < j; i += 4, j -= 4) {

temp = rk[i ]; rk[i ] = rk[j ]; rk[j ] = temp;

@@ -1125,27 +1125,27 @@

for (;;) {

t0 =

Td0[(s0 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(s3 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(s2 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

- Td3[(s1 ) & 0xff] ^

+ Td1[(s2 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(s1 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td3[(s3 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[4];

t1 =

- Td0[(s1 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(s0 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(s3 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td0[(s3 >> 24) ] ^

+ Td1[(s1 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(s0 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

Td3[(s2 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[5];

t2 =

- Td0[(s2 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(s1 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(s0 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

- Td3[(s3 ) & 0xff] ^

+ Td0[(s1 >> 24) ] ^

+ Td1[(s3 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(s2 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td3[(s0 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[6];

t3 =

- Td0[(s3 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(s2 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(s1 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

- Td3[(s0 ) & 0xff] ^

+ Td0[(s2 >> 24) ] ^

+ Td1[(s0 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(s3 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td3[(s1 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[7];

rk += 8;

@@ -1155,27 +1155,27 @@

s0 =

Td0[(t0 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(t3 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(t2 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

- Td3[(t1 ) & 0xff] ^

+ Td1[(t2 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(t1 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td3[(t3 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[0];

s1 =

- Td0[(t1 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(t0 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(t3 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td0[(t3 >> 24) ] ^

+ Td1[(t1 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(t0 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

Td3[(t2 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[1];

s2 =

- Td0[(t2 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(t1 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(t0 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

- Td3[(t3 ) & 0xff] ^

+ Td0[(t1 >> 24) ] ^

+ Td1[(t3 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(t2 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td3[(t0 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[2];

s3 =

- Td0[(t3 >> 24) ] ^

- Td1[(t2 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

- Td2[(t1 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

- Td3[(t0 ) & 0xff] ^

+ Td0[(t2 >> 24) ] ^

+ Td1[(t0 >> 16) & 0xff] ^

+ Td2[(t3 >> 8) & 0xff] ^

+ Td3[(t1 ) & 0xff] ^

rk[3];

}

#endif /* ?FULL_UNROLL */

@@ -1185,30 +1185,30 @@

*/

s0 =

(Td4[(t0 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

- (Td4[(t3 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

- (Td4[(t2 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

- (Td4[(t1 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

+ (Td4[(t2 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

+ (Td4[(t1 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

+ (Td4[(t3 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

rk[0];

PUTU32(pt , s0);

s1 =

- (Td4[(t1 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

- (Td4[(t0 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

- (Td4[(t3 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

+ (Td4[(t3 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

+ (Td4[(t1 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

+ (Td4[(t0 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

(Td4[(t2 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

rk[1];

PUTU32(pt + 4, s1);

s2 =

- (Td4[(t2 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

- (Td4[(t1 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

- (Td4[(t0 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

- (Td4[(t3 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

+ (Td4[(t1 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

+ (Td4[(t3 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

+ (Td4[(t2 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

+ (Td4[(t0 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

rk[2];

PUTU32(pt + 8, s2);

s3 =

- (Td4[(t3 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

- (Td4[(t2 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

- (Td4[(t1 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

- (Td4[(t0 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

+ (Td4[(t2 >> 24) ] & 0xff000000) ^

+ (Td4[(t0 >> 16) & 0xff] & 0x00ff0000) ^

+ (Td4[(t3 >> 8) & 0xff] & 0x0000ff00) ^

+ (Td4[(t1 ) & 0xff] & 0x000000ff) ^

rk[3];

PUTU32(pt + 12, s3);

}

diff -ru aes/rijndael-alg-fst.h code/rijndael-alg-fst.h

--- aes/rijndael-alg-fst.h 2000-12-06 18:50:46.000000000 +0100

+++ code/rijndael-alg-fst.h 2022-04-05 15:23:49.408531739 +0200

@@ -34,8 +34,8 @@

typedef unsigned short u16;

typedef unsigned int u32;

-int rijndaelKeySetupEnc(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits);

-int rijndaelKeySetupDec(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits);

+int rijndaelKeySetupEnc(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], int Nr, const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits);

+int rijndaelKeySetupDec(u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], int Nr, const u8 cipherKey[], int keyBits);

void rijndaelEncrypt(const u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], int Nr, const u8 pt[16], u8 ct[16]);

void rijndaelDecrypt(const u32 rk[/*4*(Nr + 1)*/], int Nr, const u8 ct[16], u8 pt[16]);